Foxfeather preparing to graft bee larvae – part of the process of raising queen bees.

Having been pretty enraptured by the bees and really enjoying our apiary, the next logical step for us was to explore the idea of breeding our bees and raising our own queens. Right now we (and most folks in the Midwest) get bees from large commercial operations in California or Georgia, but it would be nice to work on developing local stock and being less dependent on bees shipped in from across the country. On a commercial scale this would be pretty much impossible, since the optimal time for raising queen bees (summer) and starting new colonies (spring) does not match up – it is going to take some special management to make it work, but it is possible! We are really lucky to have the University of Minnesota relatively local to us and to get accepted into their yearly queen-rearing classes.

Grafting is the process of transferring teeny, tiny, delicate, day old bee larvae from where they were laid in the comb into special cells which will then be raised by the bees as queens and not worker bees. Any female bee egg laid has the potential to become a queen or a worker, depending on what it is fed, so this method of queen rearing focuses on stimulating the bees to raise the queens themselves.

Thanks to the bee lab, we were able to see the results of our grafting efforts through a microscope and screen. Magnified, you could see the larvae breathing! It was really confidence building to know that you hadn’t hurt them in the delicate transfer process. I got 8 out of 8 successfully moved – apparently I have a hitherto unknown talent somewhere there.

Another part of the practical part of the course was learning to mark bees with paint – here I was practicing on a drone (who are easier because they can’t sting). I managed to progress to marking young worker bees. It is important to mark queens in a breeding program so you can be sure the queen you are breeding from is the one you think – and not a replacement you just didn’t notice.

This is Marla Spivak, one of the teachers of the classes (and an incredible bee researcher at the U!). She is removing bars holding queen cells with transferred larvae in them we left overnight for the bees to feed and work on.

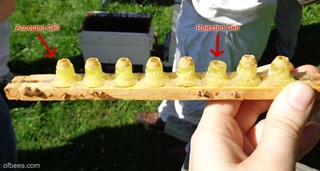

Here is the results of my grafting, 7 of the 8 larvae were accepted by the bees! You can see the progress they made putting wax around the cells. Inside the larvae were swimming in white royal jelly, fed by young nurse bees.

This is the final product of the grafting efforts – a fully capped and mature queen cell. The queen is pupating inside, spun in a silk cocoon and soon to emerge! It only takes 15-16 days from the time an egg is laid to when a queen bee emerges (less time than it takes for the workers or drones by quite a bit!).

This party-crasher at the class is actually not a bumblebee, but a mimic fly, probably of the Laphria family. Nature is amazing. ![]()

The queen rearing process is quite complex, we might try breeding from one of our hives next summer but it might take us a few years to get more established in it. since we are such a small operation. The whole thing is fascinating, though, and I am glad we had the chance to take the course!

You can find out more about the University of Minnesota’s beekeeping classes here: http://beelab.umn.edu/Education/index.htm

June 28th, 2014

June 28th, 2014  Foxfeather Ženková

Foxfeather Ženková

Posted in

Posted in